Killer Art

- Dean Cade

- Dec 19, 2025

- 4 min read

In the winter of 1997, I was out with my friend at Pacific Street, a leather/Levi bar, when I discovered the disturbing story of Elmer Wayne Henley. It was a weeknight, and the bar was sort of dead, so we went outside to the back patio and ran into this older guy, a local painter, who was smoking a joint. Stoned, he ranted about an upcoming exhibit of serial killer art at his gallery.

The backstory was wild. He talked about how another teen, David Brooks, lured Henley to meet Dean Corll and become his next victim. Instead of killing him, the serial killer molded him into an accomplice and offered him money to bring other victims to a sex slavery ring. It turned out to be something much darker. They tricked, tortured, and killed almost thirty teenage boys in the early 1970s.

On August 8th, 1973, Henley shot Dean and turned himself in, leading law enforcement to the burial sites of the victims. During the trial in 1974, the court sentenced Henley to multiple life terms. Decades passed in prison, and he became an artist, painting serene images. A third party communicated with him and reached out to the local painter to set up the art show at the gallery. There was a lot of information in that whirlwind behind the bar, and it was bizarre and fascinating.

Then he asked us if we wanted to see the paintings before the public did. We jumped on the opportunity. It turned out that the Hyde Park Gallery was directly behind the bar, and he led us to it through a gate in the bush-lined wooden fence.

A glass and wooden patio door opened into the gallery, which was on the bottom floor of the 1930s two-story house. He switched the lights on and highlighted the paintings, which were mostly landscapes with a weird childish quality—made disturbing by who painted them. There was a partial nude that was eerie, but two others creeped me out. The juxtaposition of one painting with sunflowers and barbed wire got under my skin for reasons I cannot explain, while another of the dunes on a beach had to have been a burial ground.

As we looked on, the painter talked about technique. He also mentioned a random encounter he had hitchhiking, that Henley had picked him up, and how he was lucky to escape but unaware at the time. I doubted the veracity of the tale, but the idea and the ultra-cold air conditioning chilled me. My first impression of serial killer art was morbid fascination—a feeling I did not like.

Over a decade later, in 2010, the painter, Larry Crawford, asked me if I wanted to write about the art exhibit since there was renewed interest in the case based on DNA findings. His gallery and Henley’s paintings had been in Collectors, a 2000 documentary about serial killer art, and he was interested in telling more of his story. I told him that I would look into it and began a quest to understand the crimes.

There was not a lot of information online at the time. All I could find about the murders were some news clips from 1973 and one from a mondo documentary, The Killing of America. I had seen the film as a teenager, along with extreme stuff like Faces of Death.

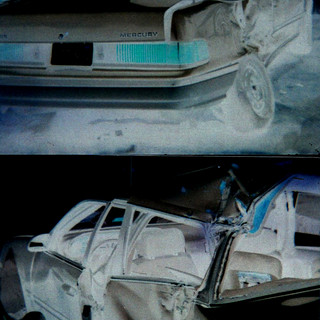

The clips showed the excavation of bodies from the woods, the beach, and the boatshed in somewhat gruesome detail. I saw footage of Henley and Brooks sitting on the crime scene beach, in the trial’s courtrooms, and behind bars. The infamous clip of Henley calling his mother on a police car phone (“Momma, I killed Dean.”) from the boatshed was also there. Nothing else came up.

The two books written about the crimes were out of print, so I went to the downtown Houston Public Library. Neither book was available for loan, so I had to go to the old library next door to read them. The building, constructed in the 1920s in a Spanish Renaissance style, was a bit rundown. The lighting was dark, the wooden steps were creaky, and the Texas Reading Room felt heavy in a strange way. The haunted atmosphere amplified my imagination while reading about the murders.

The two books, The Man with the Candy by Jack Olsen and Mass Murder in Houston by John Gurwell, both from 1974, laid out the details, the former in a more concise way than the latter. I researched in that eerie room for a few weeks, taking breaks to look at the microfiche of local newspapers.

The more I read, the more disturbed I became. The details of sexual assault, torture, and murder were crazy, and the images of exhumed, decomposing bodies were gross. I understood the motivation of a victim’s relative to buy a Henley painting at the 1997 art opening and burn it on the street in protest. I continued taking notes in my notebook and even mapped out the locations in the Heights, the burial sites, and the house where the horrors ended.

In that oppressive reading room, I became unsettled. The crimes were vile, and there was no way into the story. There were no heroes—no detective or FBI agent that solved the case—and I definitely did not want to write from the killer’s view or about the art exhibit. I did not know how to go forward.

I felt lost and almost dropped the project, but I decided I needed to see the locations in person, including the hard-to-find boatshed. I had to ask around and find a way into the story. What I discovered changed my approach, offering a ray of light in the darkness.

SUMMER 1973, a unique blend of horror and true crime, is coming on March 15th, 2026, from Slashic Horror Press.

Dean Cade