True Crime Horrors

- Dean Cade

- Nov 19, 2025

- 4 min read

The true crime genre is fascinating in its psychology, and the works range from thoughtful dramatic thrillers to horrific exploitation. I have written a series, SUMMER 1973, releasing in 2026, that falls squarely in the genre. The following is my reflection on serial killer media that has affected me over the years.

When I was a teenager, I discovered Helter Skelter on TV and was mesmerized. I had never seen a courtroom drama that dripped with such insane intensity. The tone intrigued yet disturbed me, and the viewing turned me on to the book, which held the same vibe.

The next high water mark of the true crime genre came at the end of my adolescence with the controversial, unrated release of Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer. The MPAA had refused to give the film an R rating due to its tone. No cutting of scenes would change the ruling. I saw a screening in its limited run and had to show my ID to prove that I was over seventeen. The film was disturbing but well done. The scene that haunted me was the aftermath of a broken Coca-Cola bottle jammed into a prostitute's face. The sounds of the attack played over the image as the camera zoomed in, with the ominous soft pitch of the score rising underneath, which was truly creepy.

Around that time, I used to purchase bootleg videos from the ads in the back of Fangoria. The VHS tapes I bought were mostly foreign and indie films, and sometimes there’d be trailers and footage of unreleased stuff. On one of the tapes, with trailers for the grungy Road Kill: The Last Days of John Martin and a Japanese torture film with images of contorted, tied-up women hanging from the ceiling and enema geysers overlaid with Carmina Burana classical music, I discovered Charlie’s Family. The grainy film footage looked like a documentary, with recreations of life at the commune-like Spahn Ranch and actual music by the family. Almost a decade later, I bought a copy of the finished film with additional “modern day” scenes and a new title: The Manson Family. The director, Jim Van Bebber, hit on an indie aesthetic that worked.

There were lots of serial killer films as the millennium turned, but most of the true crime ones were low budget. One psychological film, Dear Mr. Gacy, stuck with me. The premise of the film followed an obsessed college student who wrote and then interviewed John Wayne Gacy in prison. As the sessions continued, the student became more influenced by the killer. I liked that it took a different route and portrayed the transference of evil.

The problem with serial killer films and books is that I find it difficult to feel empathy if it is from the killer’s point of view. With that in mind, I started watching Monsters: The Lyle and Erik Menendez Story with a bias. I was radically surprised about how much I liked the story, especially the acting, as the series won me over. “The Hurt Man” was my favorite episode. Filmed in one continuous shot, the camera slowly zoomed in on Erik (Cooper Koch) as he gave a riveting monologue on his abuse with a sly hint at him being a sociopath. The Menendez brothers are murderers, but their story of abuse is complicated. They were not the only monsters portrayed in the highly watchable series.

The true crime behind SUMMER 1973 had not been documented well when I was researching the original manuscript. There were only two books, The Man with the Candy (the better one) and The Houston Mass Murders; two documentaries, The Killing of America, a mondo film akin to Faces of Death, and Collectors, which dealt with the underground world of serial killer art; some news videos from when the story broke; and newspaper microfiche in the public library. I even knew the star, Chris Binum, of In a Madman’s World, indie horror director Josh Vargas’ lost film. The rough version can easily be found online.

For a long while there was nothing more until the Mindhunter series, a deep dive into the FBI’s criminal profiling of serial killers, spotlighted Elmer Wayne Henley on episode 4 of the second season.

The rise of true crime in popular culture in the last few years has brought some renewed interest in the case, with new podcasts, books, documentaries, and news stories being released. Two projects caught my interest. One book, The Scientist and the Serial Killer, about Sharon Derrick’s path in forensic pathology of naming unknown victims and correcting past mistakes, was fascinating and disappointing as the pace slowed after she moved on. I briefly met her in 2009 at the funeral of ML73-3356 (the unidentified remains of swimsuit boy), but she was only interested in leads to solving the mystery of the boy’s identity, which is understandable. The second book, The Serial Killer’s Apprentice, dove into the psychology of Henley from being a potential victim to becoming a killer. I perused these books and was encouraged to find my horror fiction had the core of the true crime tale intact from my past research.

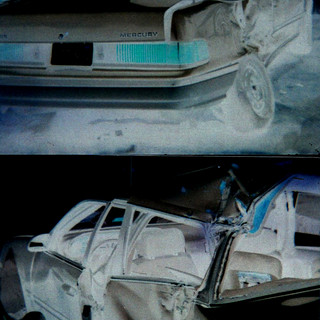

Recently, I saw the Netflix documentary film adaptation of The Serial Killer’s Apprentice and found it fascinating. Even with some recreations that were off with different-looking actors and a stand-in for the house on 2020 Lamar Street that was not exactly like the one in 1973 (the original house was torn down by the city of Pasadena, TX, in 2003), it worked. The muscle cars, the parties, and the Heights neighborhood all were akin to details I had written into my story.

In SUMMER 1973, I wanted to write about what it was like to live in a downtrodden working-class neighborhood, where teenagers were disappearing.

The real-life killers, Dean Corll, Elmer Wayne Henley, and David Brooks, are antagonists in this tableau set during the time of the Houston Mass Murders. The heart of the story revolves around my fictional protagonists, Lane and James. I gave them a secret gay life and set them in an environment and situation similar to what really happened to some of the victims. It is a fine line in crafting a story. I think the key is the interrupted lives of the protagonists and the truth that dark things really do happen.

SUMMER 1973, a unique blend of horror and true crime, is coming in March 2026 from Slashic Horror Press.

Dean Cade