Obsession Redux

- Dean Cade

- Oct 21, 2025

- 4 min read

Costumes and makeup effects have always been a part of Halloween for me. In the 1970s, when I was a kid, my mom would get me one of the simple plastic outfits from TG&Y to go trick-or-treating. Generic masks lined the shelves, including skulls, vampires, ghosts, and even a knockoff of Frankenstein’s monster. With the popularity of Superfriends, there was also a brief period of running around in Superman Underoos with a red towel for a cape, to my mom’s chagrin. As I got older, I took an interest in painting my face and using fake blood.

Fascinated with horror films, I rented VHS tapes at a 24-hour gas station, slashers like The Slayer, Maniac, and Scalps, and would watch them late into the night along with classic monsters on TV. My interest poured over into other media, including horror books and magazines. When I discovered Fangoria in 1984, I found a place to get better makeup and blood than the local store. I rented a VHS camera one October and tried doing a zombie/slasher film in my backyard. The footage was mostly terrible, with the exception of one scene where I poured fake blood over my grandmother’s head, and she looked up and said, “I hope you rot in hell.”

I read about special effects and became obsessed. It was cool to scare people or gross them out. From another Fangoria ad, I bought an authentic Halloween film replica of the Michael Myers mask with a soft horsehair mane on William Shatner’s altered likeness. I put on a gas station jumpsuit, blacked out my eyes, and stalked the scene at a keg party, scaring some girls. On a different night, I traded the outfit with my friend, Lee. We went outside my house, and I hid around the corner as he knocked on the door. The curtain moved, and he remained silent except for his heavy breathing. My mom freaked out and asked, “Who are you?” just like a character in a horror film. It turned out she was watching Halloween on TV, and her terror was real. It was glorious.

In my late teens, the culture of Halloween inspired me to try to make a film. I wrote a rough, hardcore script filled with taboos, graphic violence, arterial sprays, gore, torture, S&M, incest, and depravity—the kind of film that only a teenager in the era of Reagan youth could get behind.

The screenplay’s story involved a group of teenage campers who discover an underground lair of a supernatural killer. The cold open had Alice follow her boyfriend and his sister to an abandoned cabin. Shocked at what she discovered, she sinks into the soft earth, falling into an occult torture chamber. One by one, her friends end up in the lair, including the siblings with a connection to the killer. The story was completely over the top, and I was determined to film it.

With help from my friends, I built a torture room set in an abandoned family-owned two-story garage apartment, which I had previously used as a hideout when I was on the run with my best friend. The place had the perfect unkempt look. We built the set in the garage by cutting two diamond-shaped boards to bind the victims in chains across from each other and creating a sacrificial altar with a bright red pentagram wrapped in barbed wire. Each week we added more detail—chains, barbed wire, and accidental blood—to the set design. Our final touches included painting and etching symbols on the altar using images from the Necronomicon.

I cast my friends in the roles. It was easier getting guys than girls at first, but with a lot of persuasion, it came to pass. I cast a heavyset metal guy to play the killer, and he was psyched. I stocked up on Karo syrup, red food coloring, and Kodak Photo-Flo (Dick Smith recipe) to make a vat of fake blood. Bit by bit, I bought latex, makeup, pumps, bladders, and professional fake blood for closeup shots. Using the Tom Savini playbook, I dulled weapons, cut at different lengths, and connected pieces with wires for impalations. Some of the effects were tricky and intense, including a sickle through a breast, an impalement with spray and streaming urine, and hooked chains pulling at the flesh of two tied-up characters each time they moved. We planned to film the outdoor scenes at a cabin in New Braunfels and the rest on that set with a rental camera, shooting that summer with the hopes of finishing it by Halloween, which would have given us four months to complete the project.

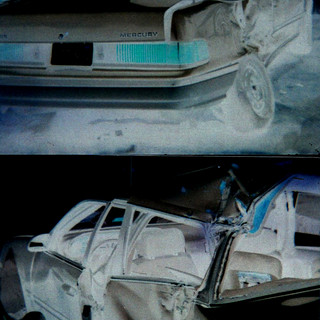

The dream of an indie horror film ended when I had a car wreck that shattered the bone in my upper right arm. My hand and fingers were in traction, using a Hellraiser-like attachment to allow my severed nerves to slowly regenerate. I felt crushed in more ways than one. I returned to the set with my metal friend, and it was unnaturally cold. (Maybe it was the real occult symbols.) It creeped us out, and we decided to leave. In Texas, the satanic panic was in full effect at the time, and some of my family were certain I had joined a cult and was worshipping the devil. I told them over and over again, “It’s only a movie,” like the tagline from Last House on the Left. I think it was easier for them to believe I was fucked up and into some weird shit rather than trying to make a film. They wanted to sell the property, so I dismantled the set and burned the altar and my dreams in the backyard.

Halloween 1990 was low-key. Instead of celebrating Samhain, I went to the park in the dead of night to swing on one of the high swings and think about the future. Now, every time autumn drifts in, I remember with nostalgia the cool horror memories of youth, and that is the power of my early horror obsession.

Dean Cade